- Tuberculosis and Humans, Till Death Do Us Part?

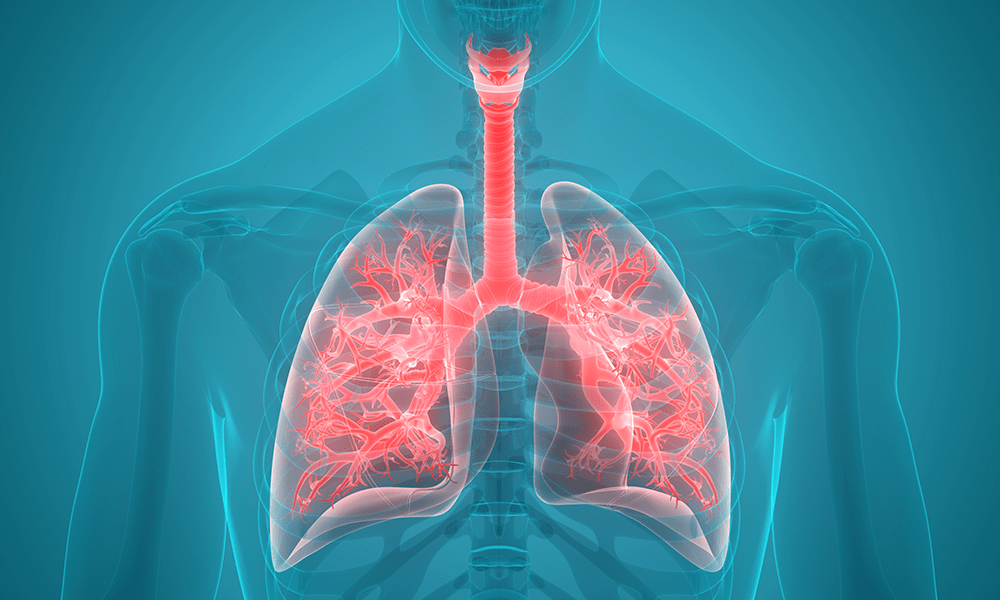

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading infectious cause of death globally, accounting for over one billion deaths in the last two centuries. The disease appears to have stuck with humans since ancient times as compelling evidence and anecdotes abound from India and China, incidentally the countries with the highest burden of the disease.

About 30 years ago, an Egyptian mummy was re-subjected to another rounds of tests, with improved performance characteristics; Mycobacterium tuberculosis was identified in her lungs, bones and gall bladder; she died in Thebes, around 600 BC. Fast forward to 2017, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that 10 million people developed TB across all countries of the world, and 1.6 million people died from the disease; this is in spite of almost a century of widespread use of the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine.

However, the TB bug appears to always be a step ahead and has successfully evaded every attempt to eradicate it, thus sustaining the coerced matrimony it has established with humans.

Dr Tunde Olayanju

Several international agencies have risen to the challenge and donated generously to the fight against TB, thousands of dollars in aids and research grants have been committed to vaccines and drugs development, the outcomes are largely incommensurate with the vast monetary investment. The WHO’s “stop TB strategy” (2006-2015) has given birth to the “end TB strategy” (2015-2035) while the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDG; 2000-2015) has metamorphosed into Sustainable Development Goals (SDG; 2015-2030), both with pragmatic intentions to fight the TB scourge. Governments of different countries have also spent substantial proportion of their health budgets to support prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of TB in different capacities. However, the TB bug appears to always be a step ahead and has successfully evaded every attempt to eradicate it, thus sustaining the coerced matrimony it has established with humans.

Not only has TB refused to go away, it has evolved over the years, altering its genome to procreate strains that are resistant to drug treatment. That becomes a bigger challenge because TB drug development appeared to have been banished into a limbo for over 40 years, while the bug had a field day playing hide and seek with the available drugs. There is currently a wide spectrum of resistance ranging from monoresistant TB, through a multidrug resistant (MDR) TB stage, to a group of strains referred to as extensively drug resistant (XDR) TB. The cascade snowballs progressively based on the number of important drugs the bug has developed resistance to, and there appears to be no end in sight. A totally drug resistant (TDR) TB has been described in literatures, and cases have been reported in India, Iran and South Africa, other authors referred to these strains as incurable (XXDR)TB; although this is not yet a conventional classification, only for technical reasons.

Rather than wait for people to present at hospitals with chronic coughs, haemoptysis and weight loss, pro-active institutions now intervene in communities, screening large number of people who would otherwise not go to the clinics, with WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic (WRD) kits, and the detection rate of active TB in those apparently healthy people has been alarming. The implication of this finding is that hospital reported incidence rate may just be a tip of the iceberg. Sadly, there has been several reported cases of primary infection by drug-resistant strains, as evidenced by whole genome sequencing showing downstream cases with identical sequencing profile and resistant-encoding mutations to index cases. Most of the affected people had been in contact with the index cases who probably had failed treatment or are battling with a recurrence. Furthermore, health care workers who are directly involved in patient care now bear a huge brunt of nosocomial transmission, and this trend has been widely reported.

Although sputum culture still retains a high sensitivity in detecting the TB bug, the caveat for a relatively high bacillary load is a major limitation in immunocompromised individuals. However, the use of urinary Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) is becoming more popular as a dependable point-of-care testing (POCT) platform in sputum smear negative patients, especially in HIV-coinfection which is very common in TB patients. Xpert Ultra has also been developed with improved assay chemistry to boost the diagnostic accuracy of gene Xpert, an automated polymerase chain reaction based rapid test for detecting TB and rifampicin resistance. Furthermore, Line Probe Assay (LPA), a rapid molecular test has been approved to not only detect TB, but also to detect resistance to major first and second line drugs, thus enhancing the early diagnosis of drug resistant TB.

These are all impressive innovations aiming to improve clinical approach to the management of TB, but will this bug ever bulge? There is hardly any known anti-TB drug currently in use, that the bug has not developed a pathway to evade. Certain countries have even made it mandatory to conduct an extended drug susceptibility testing before commencing treatment in TB patients. This is in a bid to ensure patients are getting drugs to which the bugs will respond, rather than empirically loading them with drugs which are though potent, unfortunately, ineffective in patients with resistant strains. There are already reports of resistance to novel and repurposed anti-TB drugs like bedaquiline, linezolid and delamanid even when so many countries have not been able to procure them because of the cost. If and when such countries finally muscle their ways into the elitists’ group to access the so-called novel drugs, the bug may just be far gone, as usual, one step ahead and we are back to square one.

Will TB always win over humans? Maybe there are things we could do differently or possibly just improve on. Is it possible to cast the net of diagnosis wider, for instance by intensifying effort at screening beyond pre-employment tests? The market women, artisans, prisoners and close contacts of TB patients are potential targets for active case finding to enhance early detection and possible disease containment. Treatment programs could also be strengthened, with tighter control on admission policy, directly observed treatment and antibiotic stewardship. At least 20 clinical trials are currently at various stages of completion on the registry, the regimens with proven efficacy could be fast-tracked and given early approval.

Maybe it’s also time to fully embrace Host Directed Therapy (HDT) using autophagy inducing drugs; Alternate Day Fasting (ADF) has also been recommended as a physiological way of inducing autophagy. Improving infection control measures in treatment centres would also go a long way in protecting health care workers.

Bearing in mind that vaccination has helped in the past to eliminate killer diseases and that concerted efforts and political will recently produced a potential cure for Ebola, governments and non-governmental organisations could do more to finance TB related research. More so, that human migration across continents is not likely to stop anytime soon

Dr. Olatunde Olayanju writes from Oyo State, Nigeria and can be reached via holatundey@yahoo.com.

Forex3 weeks ago

Forex3 weeks ago

Naira3 weeks ago

Naira3 weeks ago

Billionaire Watch2 weeks ago

Billionaire Watch2 weeks ago

Naira3 weeks ago

Naira3 weeks ago

Naira2 weeks ago

Naira2 weeks ago

Naira1 week ago

Naira1 week ago

Naira4 weeks ago

Naira4 weeks ago

Banking Sector4 weeks ago

Banking Sector4 weeks ago